The dangers of “go big or go home” mentality for singers

In my experience, singers fall into three main categories regarding the size of their voice:

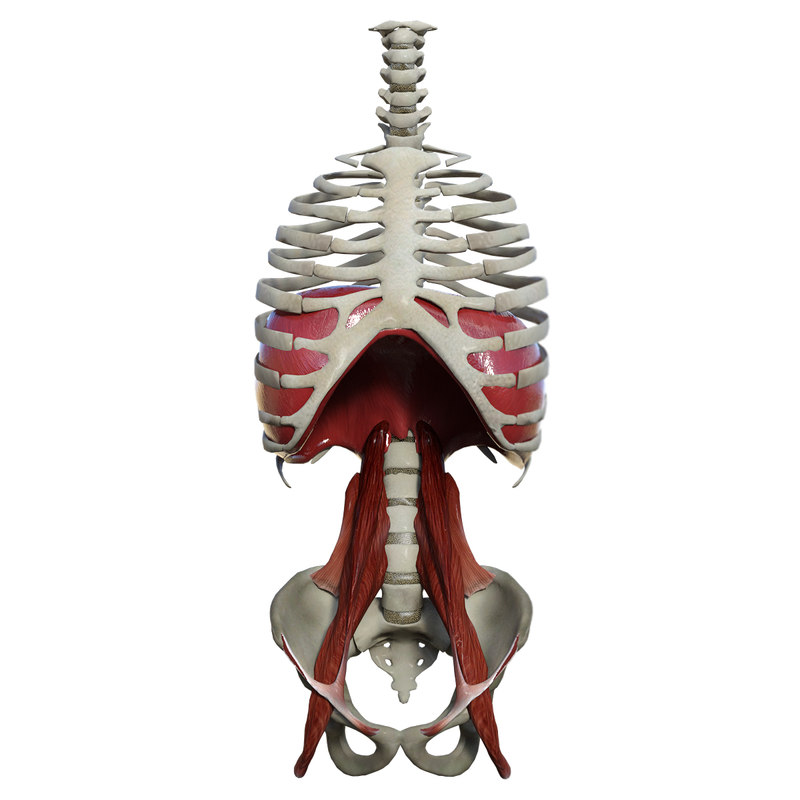

- The first category are the singers with the above average vocal cord mass (thickness) and above average strength in their larynx mechanism.

- The second category are people with average sized vocal cord mass and average strength in their singing mechanism.

- The last category of course, are people who have undersized vocal cord mass and a lower level of overall strength in their larynx.

There are other categories of course, but for the purpose of this article we’re going to keep it simple by assuming that most singers sit in one of these three categories.

In over 20 years of coaching experience, I’ve observed that the singers with above average vocal cord mass tend to sing with a natural balance to the size of the sounds they are producing. This simply means that their vocal mechanism is able to perform the various coordinations efficiently within the larynx to produce a rich, warm tonal, round sound.

In other words, good singers that are born with above average mass always sing in a way where they have control over the song. There are exceptions to these rules, but for the most part these observations are accurate.

Whereas singers that are born with average mass in their vocal cords tend to try and subconsciously and/or consciously make bigger vocal sounds than their vocal mechanism is able to comfortably support. This will create a number of vocal challenges and difficulties and will literally (in most cases) sabotage and prevent the singer from ever reaching their full vocal potential.

Those people born with smaller than average vocal cords tend to have an even bigger Napoleon complex, in other words the singer with the smaller voice often tries to over compensate and create a bigger sound than what their vocal mechanism can initially handle.

In the short term, this will show up in the singer as sung notes that sound very strained. The notes will sound dull and flat. When you understand a little bit more about the actual mechanics of singing, it’s no surprise that all of this additional, excessive pressure and tension that they’re applying to their vocal cords leads to a disappointing vocal performance. This means less paying customers in the future!

The consequences of making your vocal sounds bigger than they need to be

These consequences include:

The singer always needs to be in control of the song.

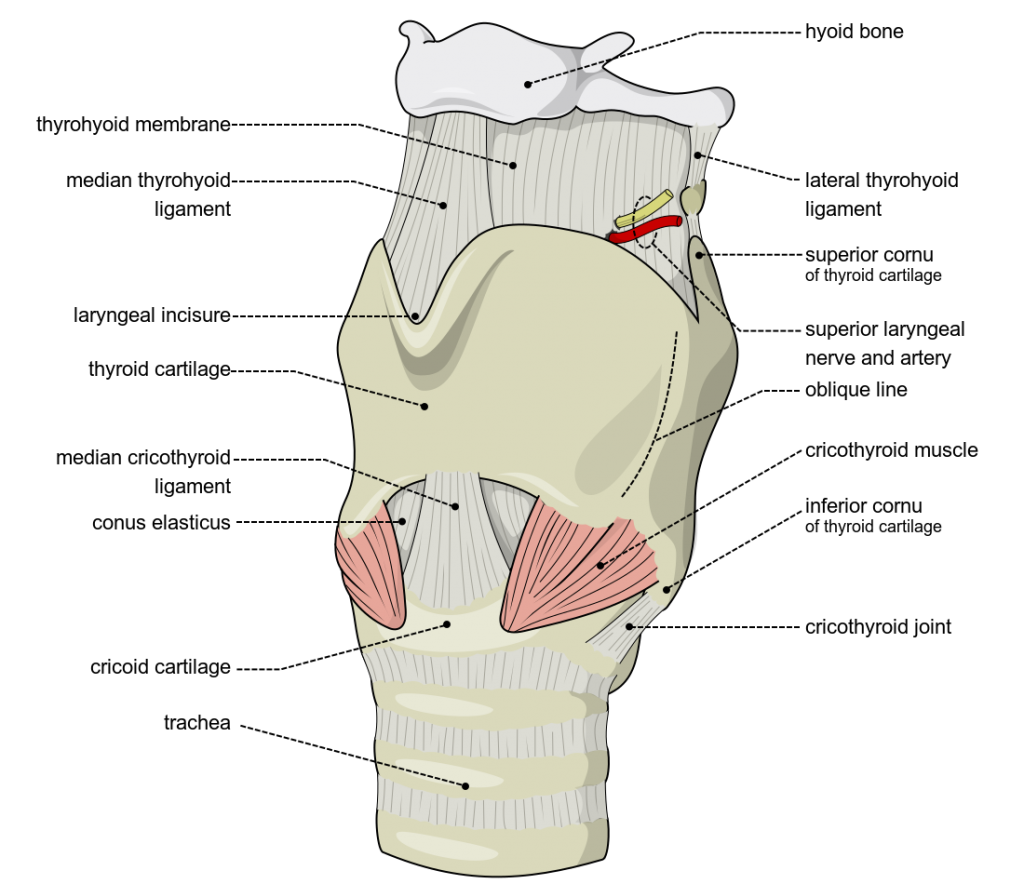

- Poor cord closure. The goal of every melodic singer is to learn how to use their vocal mechanism correctly to produce the closest thing they can get to a speech-level cord closure on pitch i.e. The notes that they sing need to have the same cord closure as a spoken phrase.

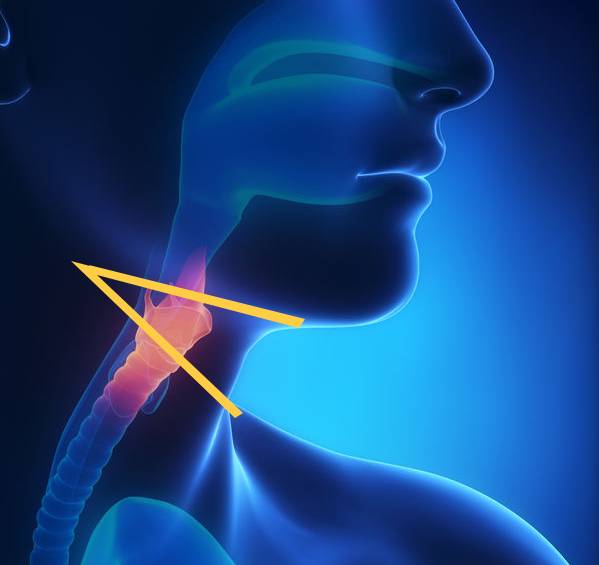

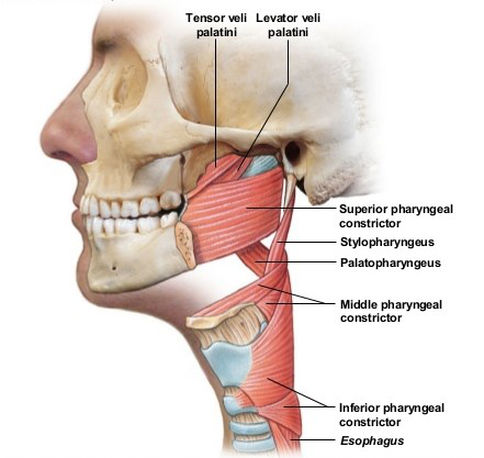

- Excessive tension. Making the sound too big and too heavy can very quickly overload the larynx mechanism and your voice will experience restriction in range. You will likely experience tension in your jaw and constriction in your throat.

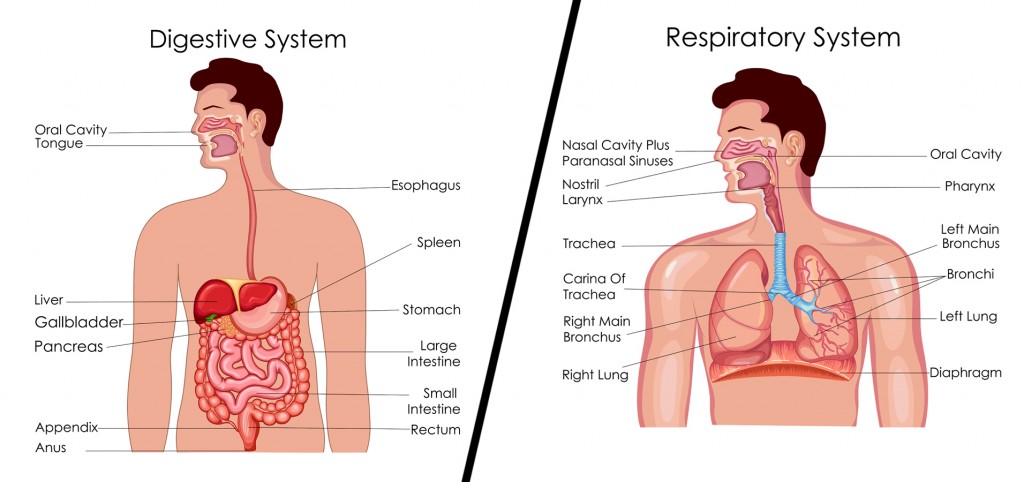

This will lead to what I affectionately refer to as the “strangled cat syndrome”. Hopefully no further explanation is necessary because every singer has experienced those exact vocal challenges at some point in their quest to sing higher and extend their vocal range. If this is you, don’t worry – you’re not alone! This is a temporary vocal affliction and it can be resolved through proper coaching instruction and through a better understanding of the role the larynx plays in efficient pitch production and changing vocal registers. - Passing excessive amounts of air through the vocal cords. This results in what we commonly refer to as a “breathy” singer. This is the equivalent of opening your mouth and aiming the air of a blow dryer into your throat. In a very short period of time, that hot air is going to dry out your vocal cords and it’s going to be dryer in there than the Sahara desert!

While some singers no doubt use this technique to achieve a smoky quality to their vocal tone, the reality is when you pass excessive air through your vocal cords, the air passing through those cords will quickly dry out your voice and remove the protective layer of “mucosa” (the singer’s lubricant that naturally protects our cords and reduces the effect of friction on the vocal cords when we sing). When we remove that protective layer of the singer’s lubricant, our vocal cords are prone to heating up, causing them to swell and become inflamed. This is a very common cause of hoarseness in singers and in some cases can lead to complete loss of voice.

Singers that prolong this style of singing i.e. who are passing excessive air over the vocal cords, be it unintentionally or intentionally, run the risk of exposing their cords to damage. This includes but is not limited to the growth of nodes (nodules), polyps and cysts on the vocal cords, among other conditions that could affect vocal performance.

Examples of “breathy” singers are Adele and Sam Smith. Both of whom coincidentally have experienced vocal conditions that have required surgery to remedy. - Limited range. If a singer is makes their vowel and consonant sounds too big, they are running the risk of overloading the vocal mechanism with excessive weight and tension that will prevent the laryngeal tilt, which is the natural mechanism in the voice, from being able to change pitch and register freely and easily as it’s designed to do.

This tends to be less of an issue in the bedroom (in front of the mirror when you’re rehearsing), but it’s a different story when you finally hit the stage and you’ve got that expectant audience in front of you and your “performer’s adrenaline rush” kicks in.

Often the combination of a performer’s adrenaline rush and any pre-show nerves will dramatically increase the potential of you experiencing the “sing big or go home” mentality. That carefully rehearsed song in the bedroom, or the shower, or the lounge where you hit all the notes and you sound like a million bucks suddenly feels like the combination of weightlifting contest and a wrestling match with your larynx.

If you find yourself identifying with the topics raised in this article and you want to take your singing to the next level, let’s have a conversation.

Better information leads to better singing!