It’s no secret that some singers are just naturally born with complementary vocal anatomy parts that make connecting to the high notes an automatic function of their voice. We often refer to these singers as being “naturals”. However if you have read any of my columns before, or if you’ve browsed my website, you’ll know that no two sets of vocal cords are the same – in simple terms no two sets of vocal anatomy (in terms of diameter and measurements) are the same.

If you’re a singer and you’re struggling to move your voice out of the bottom, or chest, register and you can’t quite find the connection between your chest voice and your head voice, which is that brighter sounding voice that singers use to sing their middle and higher notes, then this post is for you.

We need to get to know the mechanics of the voice to understand clearly what’s going on.

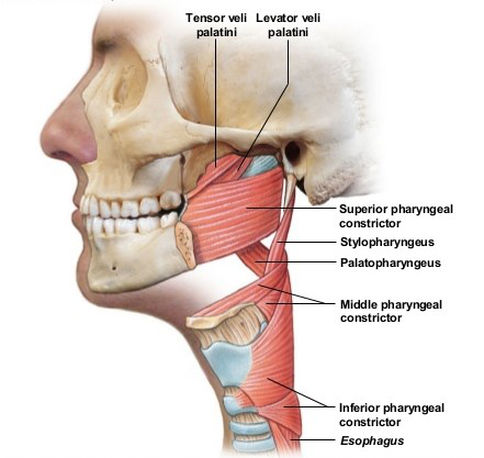

We have lifter and constrictor muscles in our throat. These muscles are largely food processing muscles that allow the throat to change shape for processing food. When we have a drink of water, the lifter and constrictor muscles allow the larynx to lift up as well as drop down, making it easier for us to guide food or water down the esophageal tube to our stomach.

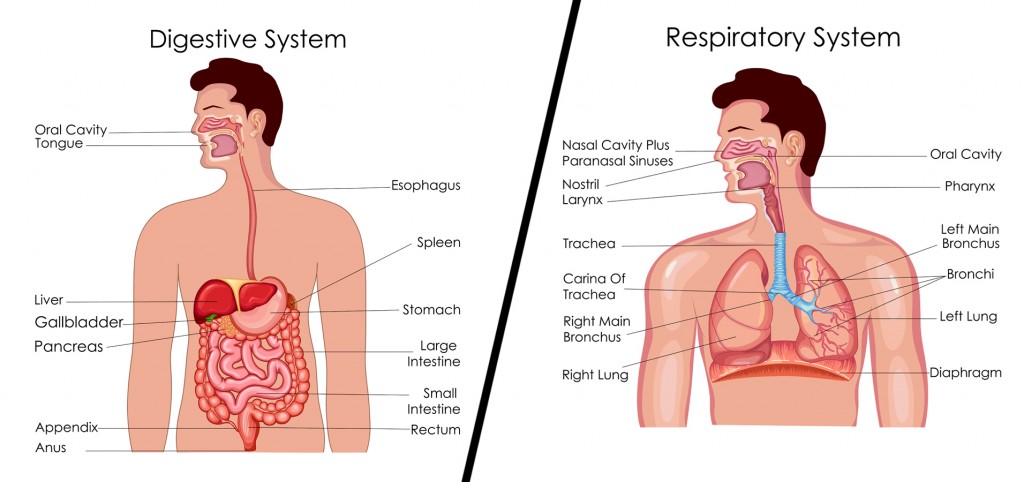

The esophagus is a muscular tube that connects the throat (pharynx) with the stomach. The esophagus is usually up to 8 inches long (about 20cm) and when you swallow food or drink water, the walls of the esophagus squeeze together, reducing its diameter, moving the food down the esophagus and into the stomach. This is kind of like how a python is able to eat its prey. The lifter and constrictor muscles help the esophagus to change its shape and get that food where it needs to go.

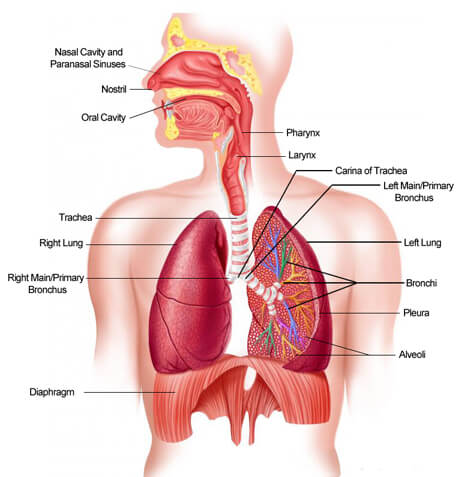

The esophagus is behind your wind pipe (trachea), which is the tube that connects your mouth and your nose to your lungs. Together, these form your respiratory system. Below your lungs is a dome-shaped muscle called the diaphragm and it’s the main respiration muscle that starts the natural breathing cycle in human beings.

The diaphragm is responsible for actioning the inhale motion, which is the action that physically draws air into your lungs, as well as the exhale motion.

Singers often encounter struggles when physically changing registers between their warm, wide chest voice to their brighter, bell-like head voice. They feel like they’re being choked or strangled and the throat feels like it has closed down. They might find that their sound has gone from really big and wide, to a strangled, muted sound as they try to sing higher. This is all because the singer has involuntarily engaged the lifter and constrictor muscles and now the body is treating the actions as being food processing-oriented. The back of the throat is closing up and we’ve gone from creating a healthy singer’s environment, to one that is optimum for processing foods and liquids.

Closure of the throat or reducing the diameter of the back of the throat prevents the larynx from having the full range of motion necessary to complete its desired movement, which is to thin down the vocal cords and achieve a higher register (head voice).

Singer’s tip number 1

If you’re encountering resistance in your voice as you sing higher, don’t push and squeeze against the resistance. Vocally you’re going to find yourself between a rock and a hard place if you do. The more you push and squeeze against these lifter and constrictor muscles, the more they’re going to reduce the diameter in the back of the throat and the surrounding area, and the more locked-down your larynx (voice box) will become.

A more ideal solution is to learn how to release the lifter and constrictor muscles when you encounter this resistance, and have those muscles maintain a docile state. They should be both relaxed and flexible. If your larynx is to enjoy the freedom it requires to maintain a full range of motion to reach higher notes, you must learn this skill. Seek out a coach or expert in this area, as learning how to disengage automatic muscle coordinations requires skill to understand how to bypass these automatic reactions from the body.

In a future post, we’ll talk more about how the larynx operates and how to change registers.

Singer’s tip number 2

If you breath from your upper chest, you’re going to build up excess air pressure in your lungs and in your airway. This will also automatically engage those lifter and constrictor muscles, leading to further vocal challenges in navigating your range.

Learning the correct, healthy singer’s breathing coordination is a must for every singer, in every style of singing, whether it’s classical singing or extreme metal (or anything else in between). We need to learn how to use our diaphragm support and diaphragmatic singer’s breathing to create the right supportive environment to allow our larynx to function freely as air passes through it and make vocal sounds (phonation).

In an upcoming post, we’ll focus on understanding how vocal cords are designed to create different registers in your voice. In the meantime, if you’d like to find out more about mastering singer’s breathing, send me a message and let’s chat!

Hi,

Im a beginner and would love to learn more about my breathing as a singer.

Hi Priscilla,

Thank you for your coaching enquiry. This is absolutely something I can help you with.

Getting started is easy! Please email me at paule@rapidvocalresults.com as soon as you’re ready to unlock your singing potential.

-Paule