In our last post, we started to explore your vocal anatomy.

❌ Vocal myth busted! One of the biggest myths and misunderstandings that singers get tricked into believing (and it works against them) is that as you sing higher, or if you want to make your notes sound stronger, is that you need to stretch out your larynx.

If you’re looking to make it easier to connect the lowest register in your voice to the middle, or the upper register of your voice, it is mission critical to understand the role of the larynx in singing.

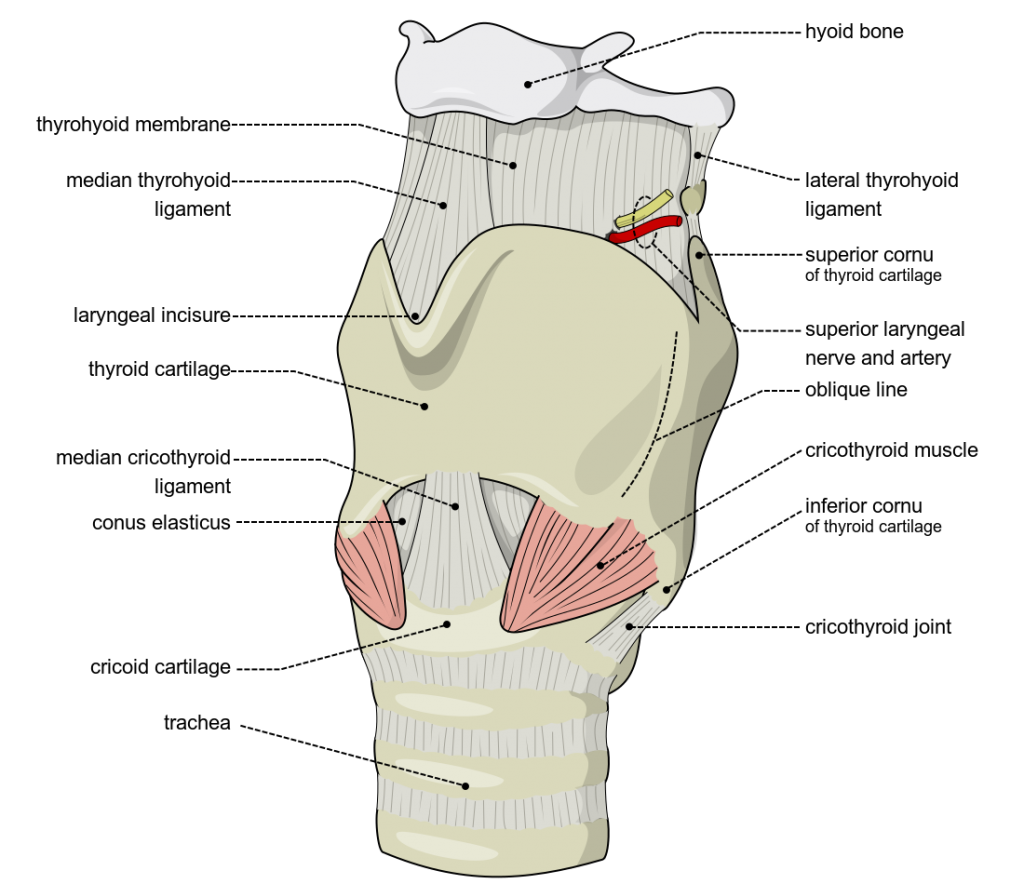

The larynx is basically a box of cartilage that houses your vocal cords. We have three larger parts of the larynx, but we’re just going to focus on the cricoid and the thyroid cartilages today, as well as the three pairs of smaller cartilages, which are the arytenoids, the corniculate and the cuneiform. We also have the epiglottis, which is a leaf-like cartilage that is the easiest to damage.

The most important parts are the epiglottis and the arytenoids. During swallowing, the laryngeal muscles contract and the epiglottis moves down to form a lid over the glottis, thereby closing off the vocal cords. This protects your airways against any stray food or drink. We’ve all inhaled at the wrong time while eating or drinking at some point in our lives. The food doesn’t necessarily make it down into the airway because our brain is hard-wired to cough and prevent the food from proceeding further.

🤓 Nerdy science fact: This is the same coordination that takes place before we lift a heavy object. When you lift a heavy object, the epiglottis moves down to form a lid over the glottis, thereby closing off the vocal cords and that column of air that gets trapped inside the body becomes the stabiliser, allowing us to continue to have good form as we lift the object. Therefore if you’re singing a high note and you hold your breath to start pushing, your central nervous system thinks you’re lifting a heavy object, locking down the vocal cords and preventing them from vibrating freely. This is the feeling of being choked or strangled that some singers experience when trying to sing high notes at full volume.

The arytenoid cartilages are able to control and change the position and the amount of tension on the vocal folds i.e. thinning the vocal folds down for higher notes and thickening up the vocal folds for lower notes.

The muscles of the larynx are skeletal muscles that form the walls of the larynx and the contraction or release of these muscles provide the movements that we associate with our breathing, swallowing and phonation (vocal sound) coordinations. The laryngeal muscles are divided into two groups; external (extrinsic) muscles, which act to elevate or depress the larynx during swallowing and the internal (intrinsic) muscles which act to move the internal components of the larynx. Both groups of muscles are vital to our control of our breathing and phonation (vocal sounds).

The external muscles of the larynx move muscles upwards and downwards. These include the suprahyoid and the infrahyoid muscles of the neck.

The internal muscles of the larynx are a group of muscles that activate individual components of the larynx. They are used to control the shape of the glottis and the length and the tension of the vocal cords. The names of these muscles are cricothyroid, thyroarytenoid, posterior cricoarytenoid and lateral cricoarytenoid, and transverse and oblique arytenoids.

The purpose of sharing this information with you is not to turn this blog into a medical anatomy blog. The purpose is to give you an understanding of these muscles so that we can get to the next stage of the conversation, which is how this affects your singing.

Most beginner, intermediate and even some professional rock star singers often fall into the trap of visualising that higher, or bigger notes require a stretched out larynx position. This is actually not the case. It is simply our brain and our ears incorrectly interpreting what they’re hearing and giving you bad advice. It’s important to understand that the psychology of singing plays a big role in impacting our vocal and breathing decisions.

Babies are able to produce high pitches for sustained periods of time and they’re certainly not stretching out their larynx to produce those sounds. The problems start when your brain and your ears get together to use some imagination to come up with a solution, because the stretched out larynx position is going to prevent the correct vocal coordinations from taking place (i.e. the thyroid tilt and the arytenoid muscles are largely responsible for thinning down the vocal cords and safely achieving that higher register in your voice).

I’m going to get you to do an exercise now to prove that stretching out the larynx is not the way to go to achieve a safe change in your vocal register.

Imagine that you are a giant. You’re 12 feet tall. How does a giant’s voice usually sound? Is it high and whiny, or is it very deep and dark in pitch?

I want you to try speaking like that giant. Chances are if you have a good imagination, your voice has dropped 2-3 notes lower than how you would typically speak.

Now try keeping the same larynx position and keep that big giant sound. See how far up in your vocal range you can go before it feels too uncomfortable to continue any further. This is an example of what happens when you stretch out your larynx.

Stretching the cricoid and thyroid cartilage out like this so you achieve an over-exaggerated opera voice is going to naturally prevent the register change taking place in your larynx. This is because you’ve taken away all of the freedom of movement that the larynx requires to achieve a register change between chest and head voice.

The reason that opera singers find it hard to sing above a high D is due to the rules that they have around how they use their larynx. For the most part, their larynx is stretched out and as soon as you create too much stress, your larynx becomes very tight, anchoring you into one register of your voice.

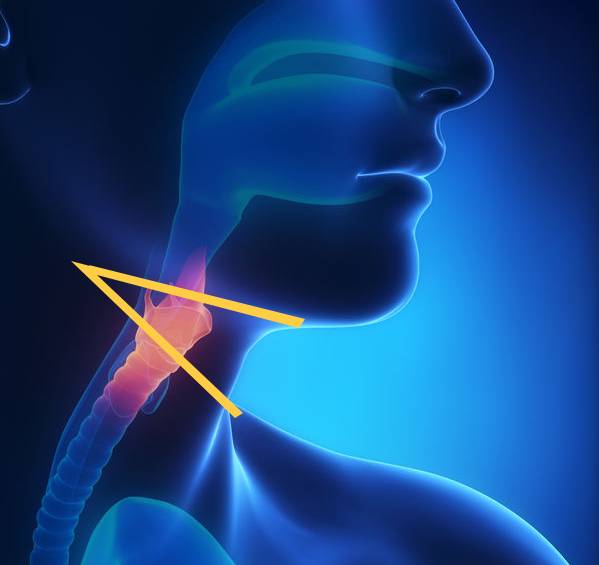

As you sing higher, you need to learn how to release your larynx setup and recreate that setup in a narrower position (all of the required components for register change are inside the larynx).

When you’re singing in a lower range and you make the mistake of stretching your larynx to try to sing higher notes, you’re not making a great connection. You’re just stretching your chest voice too far, which accompanies a thicker mass of the vocal cords. The register will not change automatically. It requires us to make some natural refinements in our singers breathing, as well as a small correction in our larynx setup to allow the larynx to shift to the correct position and allow the voice to change pitch at a natural pace.

In terms of anatomy, it is the top cartilage of the larynx (the thyroid cartilage) that tilts forward when provided with enough space and the appropriate amount of relaxation as we sing higher, and as we learn how to correctly use our diaphragm breathing to reduce the amount of excess pressure in the cords to allow the tilting of the thyroid cartilage.

It is the thyroid tilt that allows us to change register painlessly and naturally, allowing us to reproduce the same notes at a higher octave. There’s a bit of magic going on here because the vocal cords have naturally thinned down due to a combination of the arytenoids, reduction of air passing through the cords and this thyroid tilting process. This is so important because for a lot of singers, even if they can get that thyroid cartilage to tilt, they don’t allow it to tilt far enough and it’s like being straddled on a fence between chest voice and high head voice, half in and half out of the higher register.

It must be underlined right here and right now: Do not use brute force pushing or squeezing to facilitate the thyroid tilt. All you’re going to do is create a bunch of unwanted muscle contractions that will lock your larynx down. The goal here is to create relaxation to create the correct environment for your thyroid cartilage to tilt forward and begin the process of thinning down your vocal cords.

All anatomy is slightly different. An as example, shorter people and taller people have different vocal anatomy. Shorter people have thicker tendons and ligaments to anchors the cartilages of the larynx in place and they have less travel requirements to allow that thyroid cartilage to tilt forward. Taller singers with longer necks are going to need to manage that process more delicately and more precisely to allow the larynx to be in the right position to allow that thyroid cartilage to tilt. It’s no secret that the world’s top singers (especially in males) are usually 5’10” and under (5’5″ for women).

If you’re a taller person, you can learn how to develop the correct coordinations, but it requires more finesse and precision to create the right kind of larynx position to allow this thyroid tilt to happen. This can happen in any healthy voice. With very few exceptions, every average healthy voice is capable of these coordinations and can achieve a 3-octave connected range. Some singers will find these coordinations on their own, but the majority will not without proper coaching.

Learning the correct muscle coordinations to relax the larynx and allow it to sit slightly higher in a narrower setup is often made more challenging by our own brain because our brain incorrectly says to us, “As we sing higher, we need to stretch the larynx further to get those big sounds out!”. This causes all kinds of unwanted muscle tension, strangling the voice and preventing us from singing into the higher register.

Learning how to ignore your brain’s natural, unhelpful impulses and messages to stretch that larynx out can be a very frustrating process. If you haven’t already worked it out for yourself, I highly recommend that you seek out a good, knowledgeable vocal coach that can fully demonstrate these coordinations and can help you to learn the correct, higher larynx position and the accompanying thyroid tilt.