The diaphragm explained

Sting, the singer from the rock group The Police once wrote, “Every breath you take, every move you make, I’ll be watching you.” Every breath we take starts naturally by using our diaphragm.

Human beings are born into this world with natural diaphragmatic breathing, and through various conditioning agents, i.e. nurture and nature, and through the subconcious modelling of our grandparents, parents and school teachers, it’s very common that by the age of 10, most people have fallen out of using diaphragmatic breathing in favour of inefficient upper chest breathing.

The reason for this is very simple. Diaphragmatic breathing provides a very powerful, efficient fuel and support system to project a loud voice. If you’ve ever been to a primary school during recess, you can be forgiven for putting your hands over your ears to block out the deafening sound of one hundred young kids all screaming, yelling and shouting at once. At five years old, these kids are using their diaphragmatic breathing naturally, and the result is a loud, powerful voice that projects effortlessly.

Obviously this is not an ideal volume level for most households, so kids are often encouraged to learn how to speak without yelling. The majority of children by the age of 10 have been so regularly conditioned to speak quietly and not raise their voice when they get excited. By doing so, they’re learning how to breath inefficiently into the upper chest to achieve a quieter voice. Ironically, this system of upper chest breathing often leads to creating children with higher levels of anxiety, and they also experience a vocal or personal disempowerment.

Diaphragmatic breathing supports higher athletic performance

When an athlete is performing at their personal best, they are relying heavily on natural diaphragmatic support because when your diaphragmatic breathing is engaged, your diaphragm actually expands in your body, making it possible to lift more weight, to run faster, to jump higher, to kick a ball further. You can see how if someone is referred to as a natural athlete, what’s going on as well as the improved physical coordination skills and mental awareness that they usually possess, they are strongly connecting to their diaphragmatic breathing and support system to produce above average results.

Maintaining your diaphragmatic health is essential for everyone, whether you sing or not.

Nerdy anatomy stuff – to satisfy those singers among us that need to know how things work

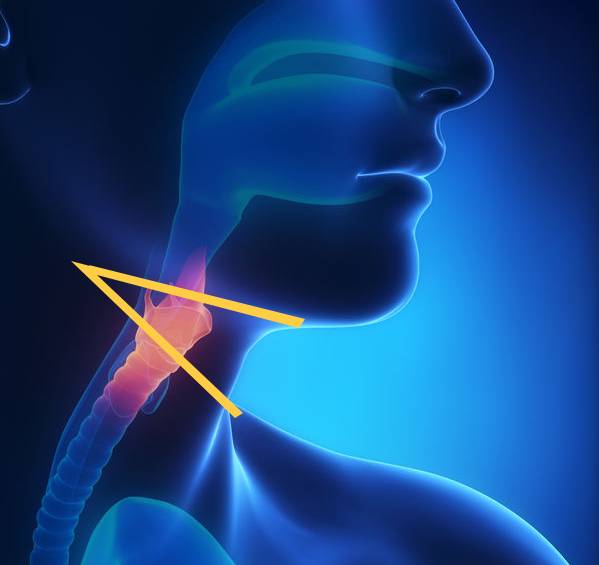

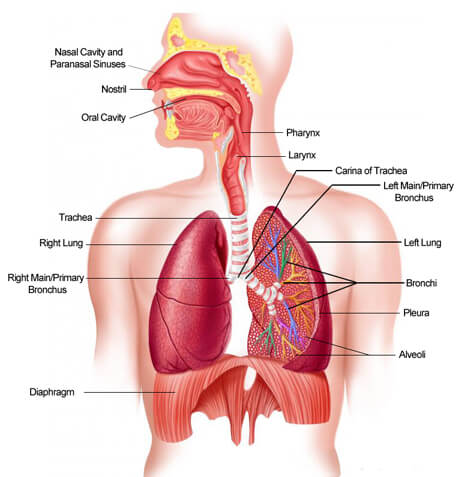

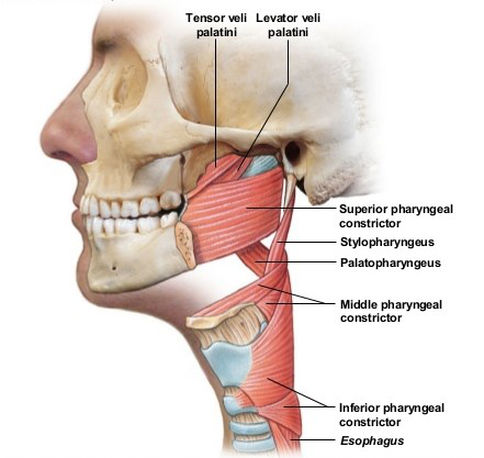

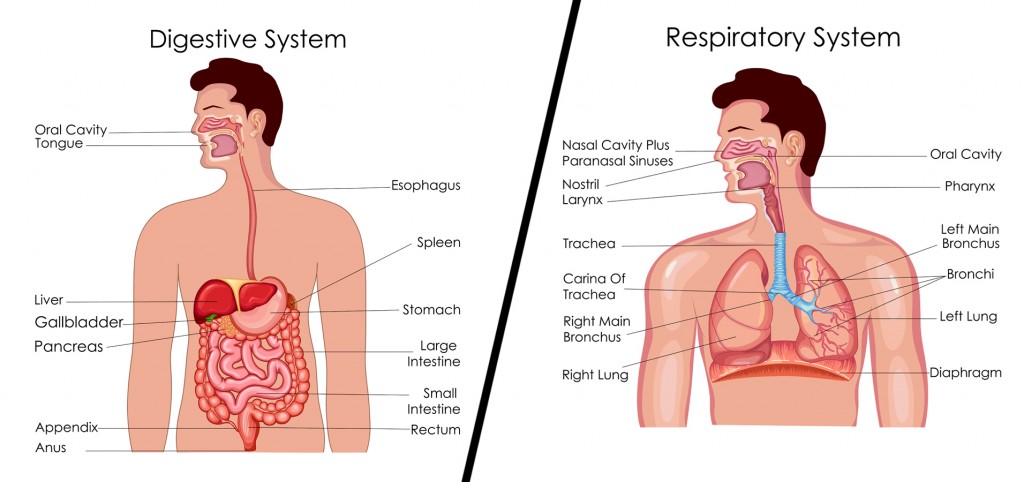

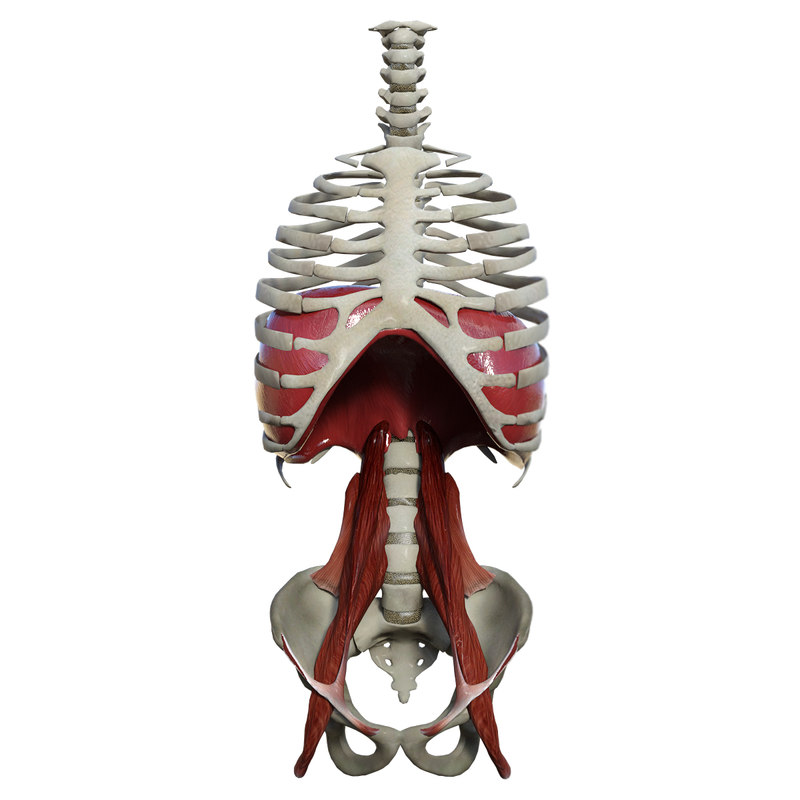

The diaphragm is a parachute-shaped, fibrous muscle that is located between your chest and abdomen, underneath your sternum. The diaphragm serves to separate the thoracic cavity where your lungs are, and your abdominal cavity where your body’s internal organs (like your stomach) are.

There are three openings within the diaphragm. Under the caval hiatus, there is the Vena Cava and the terminal branches of the right phrenic nerve. Under the oesophagael hiatus you have the oesophagus, the right and left vagus nerves and the oesophagal branches of the left gastric artery vein. Under the aortic hiatus, you have your aorta, your thoracic duct and your Azygous vein.

Quick fact: The right dome of the diaphragm is usually larger than the left dome.

The benefit of singing from the diaphragm

The benefit of singing from the diaphragm is that you immediately begin to recruit natural diaphragmatic support. In the simplest terms possible, it means that the diaphragm initially contracts down on itself. You create more space for your lungs, which makes the breath feel lower and more centered. We can then apply some gentle downward pressure on the diaphragm to slow down the diaphragm’s ability to release back to normal position, which in turn slows down the process of emptying the lungs of air. This is commonly referred to in singing as “engaging diaphragmatic support”.

The benefit of diaphragmatic support is that as the diaphragm contracts during the inhalation cycle, the diaphragm actually expands and becomes thicker. It increases the quality of compression in the air that we are passing through our vocal cords when we exhale. This basically means that the compressed air that is passing through our vocal cords is providing our vocal cords with far more energy than an upper chest breath can muster. The result is additional projection and power in our voice, meaning that we can sing higher notes for longer periods of time due to this improved vocal support.

Another benefit is that diaphragmatic breathing allows us to pass smaller volumes of air over the vocal cords, so that we don’t end up over-filling our lungs at every opportunity. If we over-fill our lungs, all the air that we take into our body needs to go somewhere and it ends up building up in the narrowest part of our lung at the top, which ends up blocking our airway with high pressure air. This causes our vocal cords to get blasted by the equivalent of a powerful tornado and the more that the vocal cords react to this pressure, the tighter they become. This results in the singer experiencing choking or the feeling of contortion in their throat and also in their voice.

So how does it feel? Here’s an RVR coaching tip

When you correctly engage your diaphragm in the inhalation breath, it feels like there is a rubber inner tube around your midsection, just under your sternum. When you lean into this diaphragm support, you start to naturally notice as you sing higher that the notes begin to float up with ease. This reduces the strain or weight that you feel in your throat. Compared to an incorrectly sung, unsupported note, the difference will feel like night and day.

Without diaphragmatic support, as you begin to sing higher, or as you begin to sing with more volume, the muscles in your throat will begin to strain and contract. A singer will commonly feel this as pressure, or weight in their throat. This provides you with a false sense of support that very quickly does more harm than good. This is because as muscles begin to contract, we can’t control the degree of contraction. The muscles will react in an exaggerated manner, reducing the available width in your wind pipe. Once this process starts, you lose control of the degree of pressure than you apply, which can shut your voice down and leave you with the feeling of a constricted airway, similar to what you may experience when lifting heavy weights.

When you sing with false support, all you end up doing is incorrectly engaging the muscles in your throat with a series of unwanted muscle contractions that may support three or four mid-range notes in your voice, and give you a false impression of power. However as soon as we increase our vocal range, the extra demand from these muscles in the throat will suddenly turn into excessive muscle contractions, squeezing the life out of our singing voice. Ironically this will result in choking off both your potential power and your additional natural vocal range.

In comparison, when you engage diaphragmatic support you engage an expanded diaphragm that to an average singer feels like a rubber inner tube around your middle (located at sternum height) that feels very much like a Whoopie cushion. As you gently exert a little bit of downward pressure, or lean into your diaphragm, your voice suddenly experiences a feeling as your notes start to float up and your throat starts to open up and relax. You will enjoy less tension in your throat and the diaphragm being a much bigger, stronger muscle allows you to support your voice with less strain and more ease for longer periods of time.

Singers that engage their diaphragm breathing and produce correct diaphragm support enjoy improved vocal projection. Their voice has more power and they are far less likely to lose their voice trying to sing over a loud band.

To understand natural diaphragmatic breathing, there are three phases of the breathing process that you should be familiar with.

Phase 1: The inhalation

The inhalation coordination starts with an expanded ribcage to create space and release pressure off the lungs, allowing them to fill up as the inspiration (inhalation) process begins. As it begins, the diaphragm is released, which contracts itself downwards and creates additional space for the lungs to begin to inflate.

🤓 Nerdy science fact: Lungs do not inflate themselves. Instead they are inflated through a difference in air pressure, creating a vacuum in the lungs that draws air down the air pipe.

When the diaphragm releases at the beginning of every inhalation breath, it contracts into itself which produces an immediate change in air pressure by increasing the volume of the thoracic cavity. This forms a vacuum in the upper part of the chest. The lungs have more space now and can enjoy more natural expansion. Air is naturally drawn in, as opposed to being sucked in by an upper chest breath.

Your lungs are simply sacks and don’t have the ability to draw air into themselves. The diaphragmatic movement creates a vacuum to draw air into the lungs.

🤓 Nerdy science fact: The diaphragm is actually instrumental in removing human waste from the body. It’s the part of your body that gives the “push” while you’re on the loo!

In direct comparison, an upper chest breath is inefficient because it means we are not creating the same amount of space or pressure difference, causing a smaller amount of air to enter into the top of our lungs, which is the narrowest part. Utilising a diaphragm release, we create more space at the bottom of our lungs, which creates a natural vacuum, which then in turn draws in more air.

Performing this inhalation correctly provides you with the feeling of a lower centre of gravity. If you breath in the top of the lungs, it is much harder to provide a steady stream of air that is required for good phonation (sound), and you are required to force the small amount of air that you have inhaled out of your body.

🤓 Nerdy science fact: It is possible to take in too much air! Upper chest breathing is highly inefficient and when you breath in too fast, you can take in far more air than your phrase requires for singing. This reduces the flexibility of your vocal cords, making it harder to produce a melodic pitch. This is experienced as a heavy feeling in the throat, and stiffness in the upper chest.

Phase 2: Learn how to engage the diaphragmatic support

To correctly engage diaphragmatic support, we need to expand our ribcage from a relaxed position, with our shoulders dropped down. While maintaining an expanded ribcage, we should let go of the abdominal (stomach) muscles. This will recruit the diaphragm to start contracting and begin the inhalation stage of our breath.

When you do this, you should feel that your breath goes down lower into your lungs. You’ll feel a deeper breath, not necessarily by drawing in more air, but by correctly engaging your diaphragm and achieving a natural inhalation breath.

Phase 3: Learn how to sing while correctly engaging diaphragmatic support

To beginner and intermediate singers, this can feel very counter-intuitive. This is because our brain will tell us one order of coordinations, while our diaphragm wants to operate in an entirely different way.

Since the diaphragm is the main respiration muscle of the human body, it makes sense to listen to the diaphragm and follow its natural directions to achieve the best results. Put simply, begin developing a healthy fascination for experiencing a diaphragm release before you make sound.

A really good example for this is to imagine that you’re at the best fireworks display you’ve ever seen (closing your eyes will help with this!). As the rockets shoot up into the sky and explode in a round of breathtaking effects, simply release your diaphragm and make “Oooooooos” and “Ahhhhhhhs”. Make sure that you release your diaphragm before each one of these very simple sounds.

“Oooooooooooh!”, “Ahhhhhhhhhh!”, “Wooooooooooow!”

When this exercise is performed correctly, you will have a very good sense of which physical feelings you should be experiencing in your body that will tell you that you are using healthy diaphragmatic support to improve both your singer’s breathing, and correctly engage your diaphragm to improve the power and projection of your singing voice.

The next topic in this series will be focused on understanding the exhalation phase of breathing, and how singers use the exhalation phase to sing without needing to push sound out of their voice.

Better singing everyone!